The Man the master the magic

Herbert Gentry was an expressionist painter, product of the Harlem Renaissance in New York City, the Great Depression, World War II, the GI Bill in Paris, 1950s in Montparnasse, 1960s Copenhagen and Stockholm, and the Chelsea Hotel of the 1970s. As the decades progressed he continued to exhibit and work on both sides of the Atlantic. Born July 17, 1919 in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, he was raised in Harlem where his mother began work as a chorus dancer in theater and club venues on Broadway and in Harlem in 1925. Early in life, Gentry was entranced by the music and magic of the theater, recalling vividly the performers, the dancers, the color, the costumes and lighting of Ziegfeld Showboat productions his mother performed in.

After High School graduation, Gentry was enrolled in art courses taught by WPA artists at Roosevelt High School in the Bronx and at the Harlem YMCA. Always intrigued by the visual arts, there he was exposed to modern painting. In 1939, Gentry accepted an office position at Con Edison and enrolled in business courses at New York University. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared War in late 1941, his future changed direction. Inducted into the U.S. Army in 1942, Gentry was sent to Fort Stewart, Georgia, for basic training in a segregated unit. Between 1942 and 1945, Gentry was stationed in North Africa, Corsica, France, Austria and Germany, an exposure to the world defined by new cultures, people and places. Gentry first arrived in Paris as a Black soldier shortly after Liberation, and was stationed in the Paris suburb of Crepy-en-Vallois. During these months he visited Paris at every opportunity. Later in 1945, Gentry was honorably discharged and sent back to New York. At home again, the ex-GI thought deeply about resuming the life he had left, but reflected, “I grew up seeing people from the whole world. Writers, musicians and painters in Harlem, and then my mother being a dancer, and her friends and a lot of people I met at that period in Harlem were highly creative. I was stimulated. New York introduced me to Paris.”[1] Determined to resume his art studies and paint in Paris, he spent the next nine months working and saving funds.

“I was brought up in Harlem. When I grew up there, Harlem prepared for you a city like Paris. In Harlem, we liked people from the whole world, and the first place artists from the whole world wanted to visit was Harlem. Foreign languages were not strange to us nor were different types of people”

Gentry was part of the first wave of GI Bill art students who arrived in Paris in 1946. The first year he had a dormitory room at the Cité Universitaire, but like his fellow art students, moved into little rooms in Montparnasse hotels within a year. Gentry also took the Civilization course at the Sorbonne and studied at the École des Hautes Études Sociales. He studied drawing and painting at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, along with Kosta Alex and Shinkichi Tajiri. Irrepressible, Gentry opened Chez Honey in 1948, a club-galerie in the heart of Montparnasse, in the vicinity of the café Dome and Rotonde. A gallery by day, it was a club by night, hosted by Gentry and his wife Honey, who sang nightly accompanied by arranger Pete Matz on piano. “Modern Jazz began in my place in Paris,” Gentry would boast – jam sessions included musicians Kenny Clarke, James Moody, Don Byas, Dick Allen, and Zoot Sims. A meeting place for artists and students of all nationalities; the well-known dropped by as well: Sidney Bechet , Juliet Greco, Jean Paul Sartre, Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, Orson Welles, Eartha Kitt, Richard Wright, and Boris Vian. Chez Honey closed in late 1951 when Gentry, his wife and two children returned to New York to pursue Honey’s music career. Disappointments prevailed that difficult year in New York City’s Lower East Side. His marriage disintegrated and, unable to secure visitation rights to his two children, Gentry sailed for Paris in 1953, on the same boat as Larry Potter and Beauford Delaney.

Herbert Gentry in uniform in front of Notre Dame Cathedral, about 1945

Herbert Gentry with artist friends in Paris in the breadline, about 1946-7

Herbert Gentry in Montparnasse, 1949

Herbert Gentry and sculptor Kosta Alex in Paris, about 1950

The next five years in Paris marked his transition into his life as an artist. Always part of the Montparnasse café life among the international painters, he began to frequent the café Tournon, a meeting place of Paris-resident African American writers and intellectuals, including cartoonist Ollie Harrington, writers Chester Himes and Richard Wright, and painter Larry Potter. Times were hard, and he accepted an invitation to produce shows for the American and Allied Armed Forces in France. Gentry became close with a young Danish journalist, Birgit Rasmussen. Gentry met Georges Braque, who critiqued and encouraged his painting and he made his first trips to Scandinavia.

While in Paris in 1958, Gentry was invited to exhibit at Hybler Art Gallery in Copenhagen, Denmark – a reciprocal gesture during the New Danish Painters exhibiton at the Riverside Museum in Manhattan. Gentry arrived in Copenhagen six months before the exhibition and rented the studio of Danish CoBrA painter Eijler Bille and painted. Copenhagen offered a thriving jazz scene with many African-American musicians, writers and artists visiting the city. He stayed in Copenhagen five years and the move opened the door to his life among Europeans. In Copenhagen, he was friendly with Paris-connected Egyptian painter, Hamid Abdallah and American painter Sam Kaner. Gentry and Kaner exhibited together at Leger Galerie in Malmö, in 1962. Gentry met many Danish and Swedish artists and critics, and joined Tempo Gruppen. With Tempo, he exhibited with other Northern European artist in group shows in Scandinavia and Germany. From 1958 – 1967, Gentry had solo exhibitions in art galleries in Zurich (Suzanne Bollag, 1959); Geneva (Galerie Perron, 1961): Stockholm (Galerie Aestetica, 1960); Amsterdam (Phillips Company, 1964) and Hamburg (Galerie Die Insel, 1960); and Helsingborg (Vikingsborg Museum, 1966). During this period entered the collection of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. All the while he kept his studio in Paris, where a new generation of artists and writers from Africa and the Caribbean and the USA were active - Larry Potter, Bill Hutson, Lindsay Barrett, Merton Simpson and Skunder Boghosian.

In 1963 Gentry left Copenhagen to join his Swedish wife Ingrid Stenvinkel and their son in Gothenburg, on the Swedish west coast. A year later, Herb took part in an important group exhibition in at Den Frie cxhibition space in Copenhagen. 10: Negro Artists Living and Working in Europe was curated by Copenhagen-based painter Walter Williams and Stockholm-based poet Alan Polite. The show included Beauford Delaney and Larry Potter, who had traveled to Paris on the same boat as Gentry, as well as Sam Middleton, Harvey Cropper, Clifford Jackson, Earl Miller, Arthur Hardie, Walter Williams and Norma Morgan. By 1965, Gentry and family were in residing in Stockholm, and Gentry had solo shows at Galerie Marya, Copenhagen (1967), Galerie Zodiaque, Brussels (1967), and Galerie Doktor Glas, Stockholm (1968).

In Stockholm, Gentry associated with sculptor Torsten Rehnqvist and painter Gosta Werner, with whom he shared a studio. He appreciated new friends from an older generation of Swedish artists as well, like Siri Derkert and Evert Lundquist, the Surrealist writers Artur Lundqvist and Maria Wine, and art curators and critics Carlo Derkert and Ulf Linde. Still, Herb’s travel itinerary hardly differed from the itineraries of other internationally-oriented European artists he knew. His friend, Swedish painter Bengt Lindstrom, also lived in France and Gentry often met sculptor Cark-Frederick Reutersward on the train back to Sweden.

Herbert Gentry in Copenhagen with Tuborg Brewery in the background, 1960-62. Photo by Seve Harder

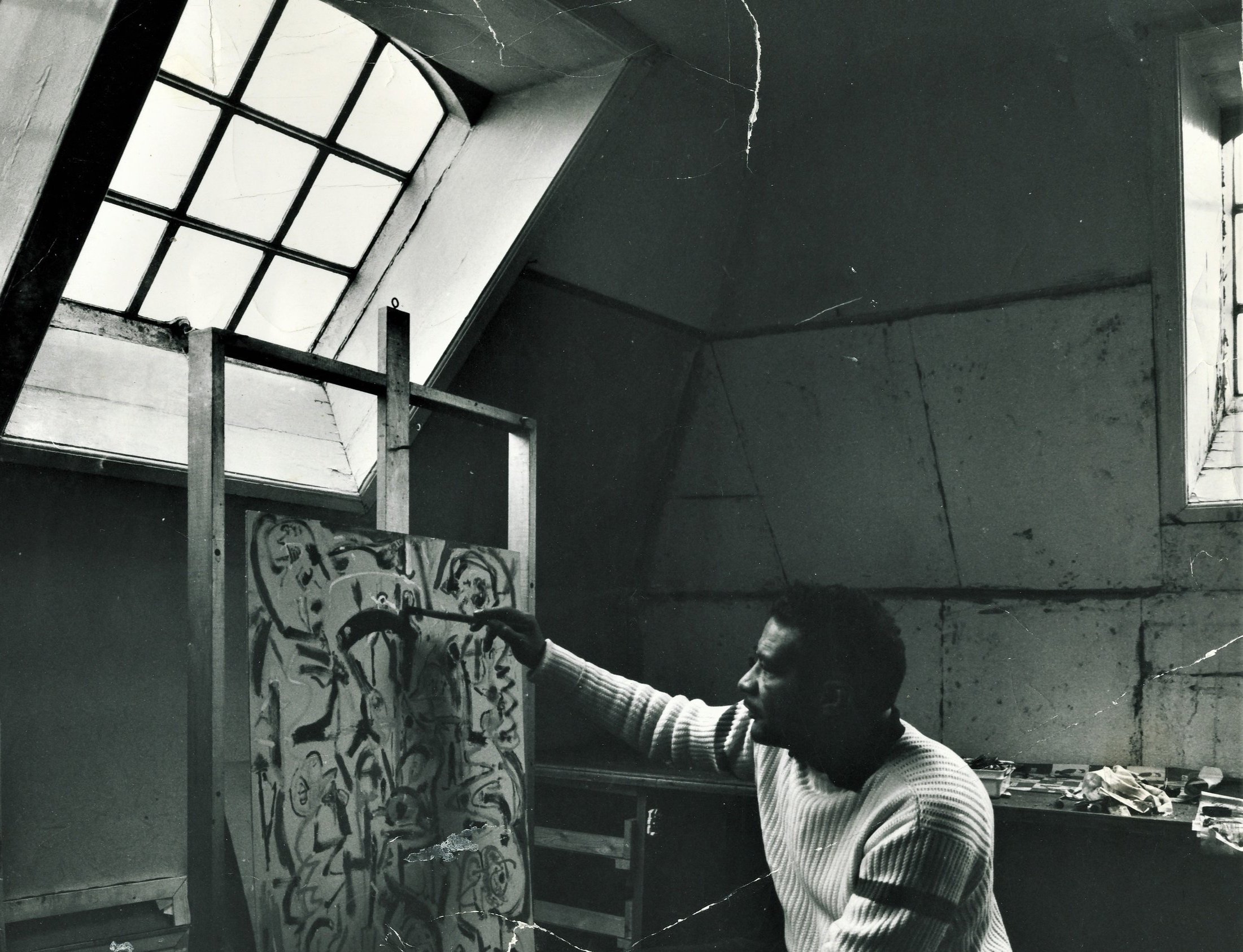

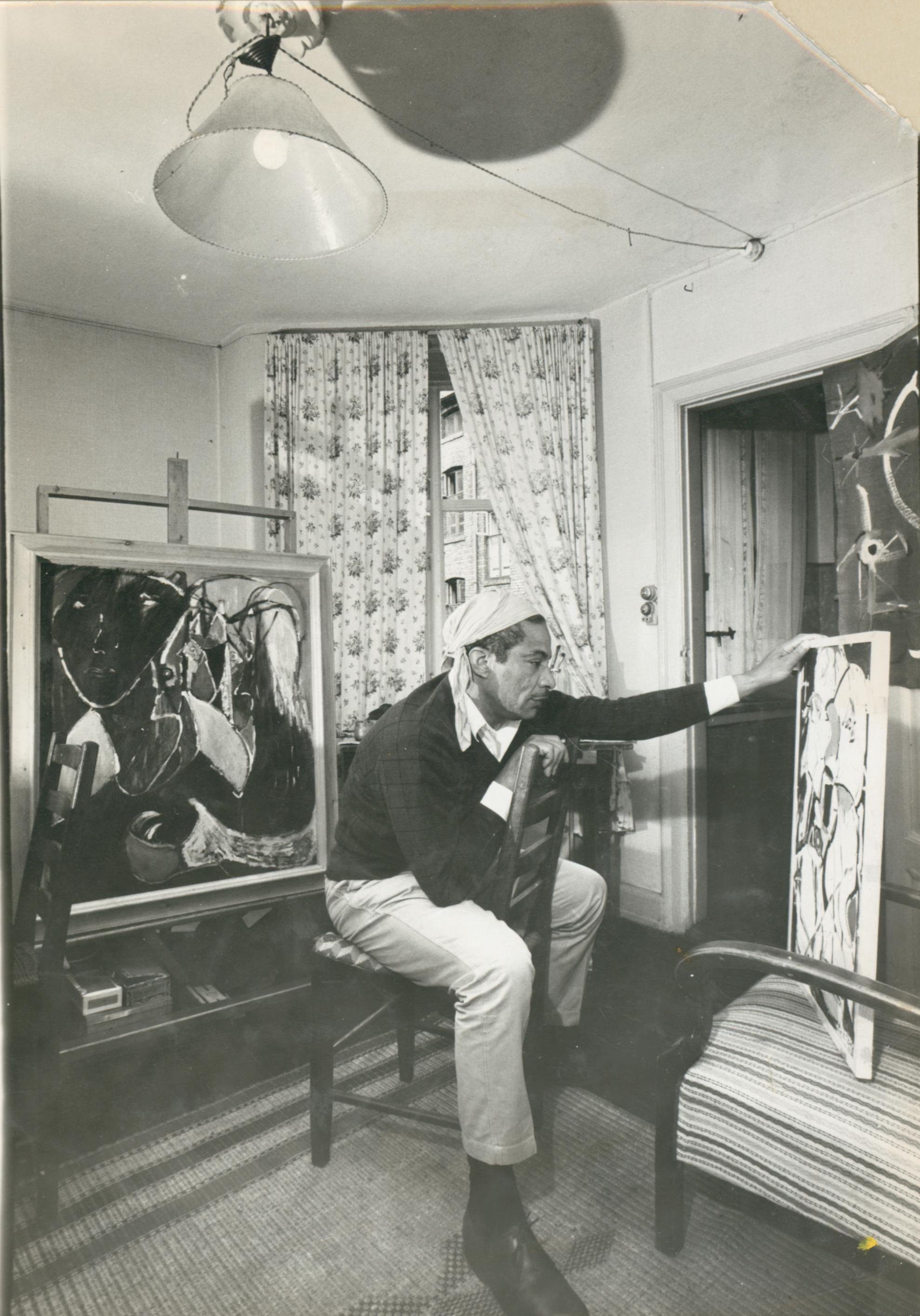

Herbert Gentry in Studio, 1960. Photo by Hubert Guillou

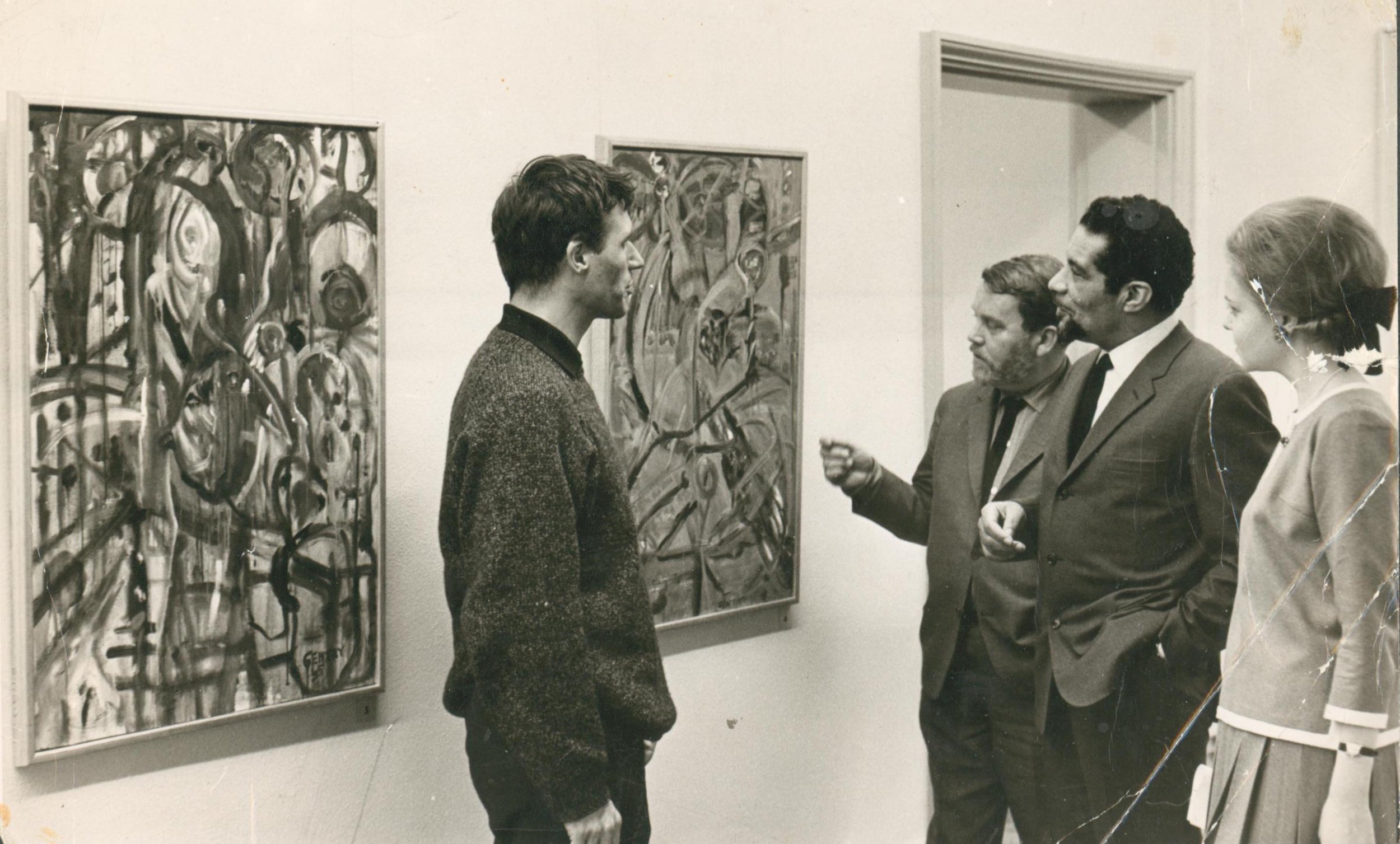

Herbert Gentry with Danish friend Ivar Soe Pedersen and Swedish artist Bengt Orup at his 1966 solo exhibition at Vikingsborg Museum in Helsingborg, Sweden

Gentry returned to New York City in 1970 and again in 1971. His work was included in Afro-American Artists Abroad, a traveling group exhibition which opened at the University Art Museum in Austin, Texas in 1970, Morgan State University Gallery, Baltimore (1970) and the Museum of National Center of Afro-American Artists, Boston in 1971. Gentry’s solo show at the Selma Burke Art Center at Carnegie Institute (1972) marked his first return to his hometown since 1945. His work was now in many museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Stockholm’s Moderna Museet director Pontus Hultén recommended Gentry take his family to the Chelsea Hotel and recommended him to manager Stanley Bard. The Chelsea was home away from home for many European artists. Gentry’s cousin Arnold P. Johnson was a new trustee at the Metropolitan Museum, and he introduced Gentry to curator Theodore Rousseau, who introduced Gentry to gallery owner Pierre Matisse. Gentry noted he was reconnecting with many who had frequented Chez Honey 20 years earlier, like Bruce Duff Hooten, who published ArtWorld from his rooms at the Wales Hotel. Merton Simpson, who had an African Art Gallery on Madison Avenue, got Gentry back in contact with artist Romare Bearden.

Chester Higgins, Hale Woodruff, Herb Gentry, Romare and Nanette Bearden at Acts of Arts Gallery on Charles Street, West Village in 1974.

Herbert Gentry at the Chelsea Hotel with Arnold P Johnson, c. 1971-72

In 1975 Gentry was honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Royal Academy (Kungliga Akademien) in Stockholm, Sweden. An Academy exhibition was a closely guarded national honor, and he was only the second foreigner to exhibit there. His retrospective traveled to Norrköping Art Museum, Norrköping, Sweden in 1976 and Amos Anderson Museum in Helsinki, Finland later the same year. During this period, the art curator for the Skandinaviska Enskida Banken purchased Gentry for many of the bank branch collections and art club purchases in the Stockholm region. The curators for the bank’s Malmö and Gothenburg districts were equally dependable collectors. Still, Gentry feared he would never achieve financial stability in just one country, inspite of the honors and successes. Gentry’s peripatetic lifestyle remained his survival strategy, even after the Academy show. By 1976, he was spending a greater part of the year in New York at the Chelsea Hotel, while based in Paris at a studio awarded by the Cité Internationale des Arts.

Installation views of Herbert Gentry: 20-year Retrospective at The Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm (January 10-February 1, 1976)

By July 1980, Gentry relocated to Humlegatan 9, Malmö with American artist Mary Anne Rose who he’d met in Paris, and worked in an attic painting studio at Amiralsgatan 45. Gentry enjoyed café life in the old town, at Café Mäster Hans or at Bro’s Jazz Café where he would start conversations with refugees and artists. There were also artist neighbors: Bertil Lundberg from Tempo Gruppen days, Uno Svensson, who had been at the Cité Internationale des Arts at the same period, and jazz singer Paula Watson. Studio Museum in Harlem curator Kinshasha Holman Conwill visited Malmö the summer of 1981 to organize An Ocean Apart: African American Artists Abroad ,which opened at the museum in 1982. American art collector Agnes Gund purchased a large Gentry painting from the Studio Museum show. Later that year, Gentry took a permanent place at the Chelsea Hotel.

Back in New York during the 1980s, Gentry was included in large group survey exhibitions presenting the history of African American Art, including Unbroken Circle, Kenkeleba Gallery (1988), New York, NY; Since the Harlem Renaissance, at Bucknell University Gallery (1984), Lewisberg, PA; as well as traveling exhibitions curated by Bob Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop, where Gentry worked in intaglio and monoprints (1977-1993).

During the 1970s Gentry had exhibited with private African American art dealers Peg Alston and Helen Jackson. In the early 1980s there were a few Black dealers who opened their own art galleries. Gentry began exhibiting with Alitash Kebede in Los Angeles and George N’Namdi in Detroit, Chicago through the 1980s and 1990s, as well as Stella Jones Gallery in New Orleans and Asake Bomani Gallery in San Francisco.

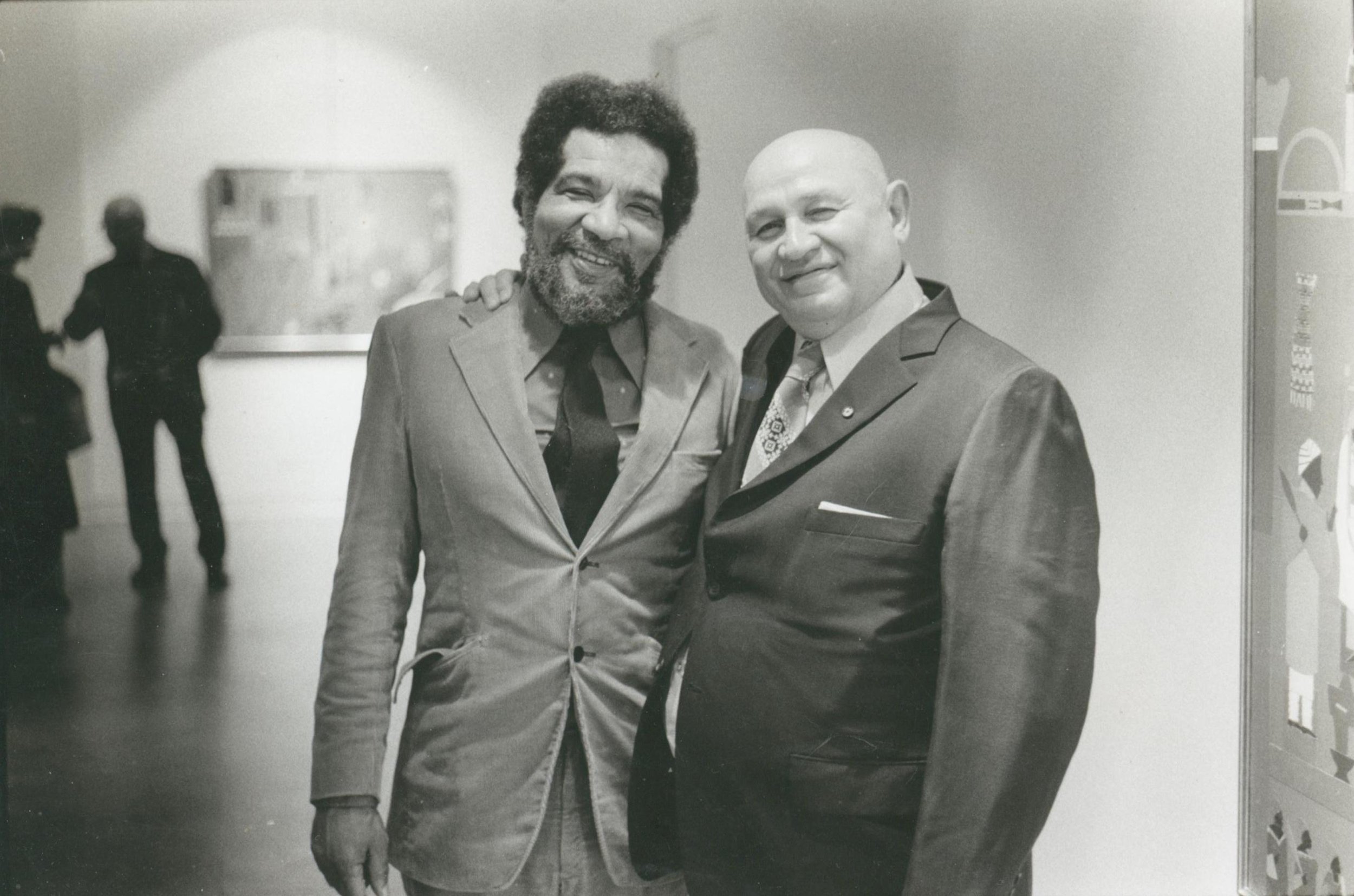

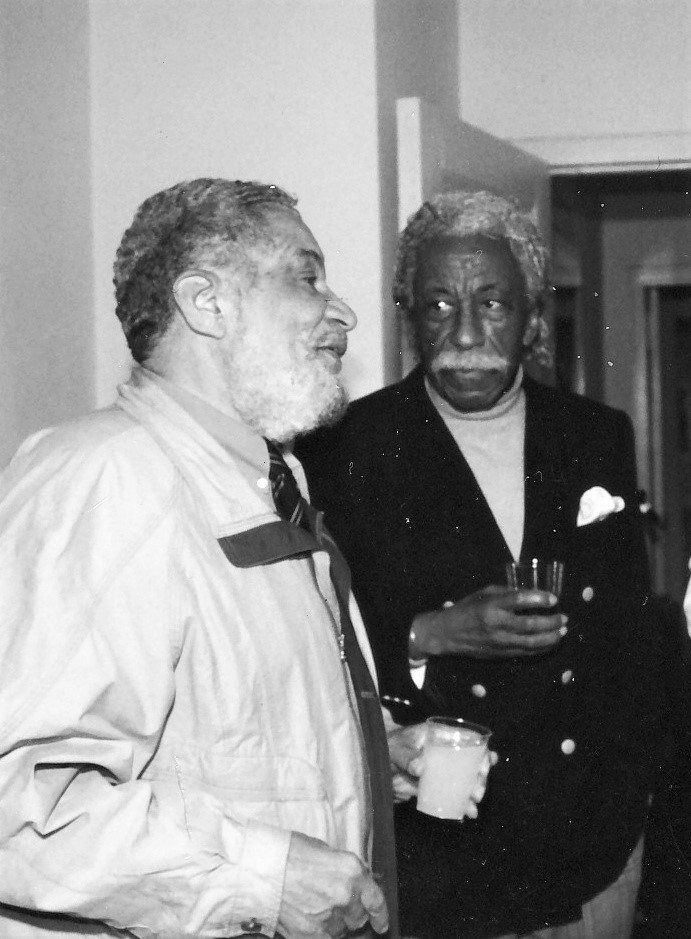

Herbert Gentry and Romare Bearden, about 1977. Photo by Adger W. Cowans

Herbert Gentry with Gordon Parks, about 1985

Herbert Gentry with journalist and poet Leonard “Skip” Malone and artist Hamed Abdalla at Den Frie Konsthall’s 1964 opening "10 American Negro Artists Living and Working in Europe". Photo by Kirsten Malone

Gentry’s international artist friendships were often the source of gallery introductions and shared contacts. Danish art critic and painter Jens Jorgen Thorsen wrote the introduction to Gentry solo exhibition at Gallery Asbaek, Copenhagen (1983). In 1984 there were solo exhibitions in at Galerie Del Naviglio, Milan (introduced by Kosta Alex) and at the Biblioteca Nationale (introduced by painter, Guy Harloff, of the Chelsea Hotel and early Paris days in Montparnasse). Many connections were now transatlantic. Old friend from Copenhagen, the African American Expat writer Skip Malone came with Danish Television to gather footage for Core of the Apple (1985) a 3 hour program highlighting African American culture in the New York city, which featured a film segment with Gentry and Romare Bearden collaborating on a painting in Bearden’s Long Island City studio: “We didn’t paint this! We danced it!” remarked Gentry gleefully.

Gentry was in Malmö when Romare Bearden died in the winter of 1988. Days later, Gentry was badly injured in a car accident caused by black ice on the way to Stockholm. When Gentry turned 70 the following year, he was fully recovered from his injuries and had reason to celebrate. After solo exhibitions at Bulowska Gallery in Malmö (1987, 1991), and Gallerihuset in Copenhagen, Stockholm art dealer Peder Olin featured Gentry in solo shows at Futura (1989, 1993). Each year when summer heat arrived in New York, Sweden beckoned with its cooler climate where Gentry had important solo exhibitions in the Skane summer colonies, at Falsterbo Konsthall (1992) and at MADDAM Ragnarpers Exhibtion Space in Gärsnäs (1993).

“All the passions I am feeling are present, yet the unwanted events that I must confront daily are there also, photographed in my conscious and unconscious, surfacing to contribute in giving the work its aesthetic balance. ”

Swedish summer with Herbert Gentry working at the beach, about 1975

Gentry painted on un-stretched canvases - folded into suitcases they became transatlantic canvases worked on two continents. His painting studios in New York changed every few years, whether in the Chelsea Hotel or nearby Chelsea on 23rd Street or West 27th Street, on Fifth Ave by the Empire State Building, or the Tuck-it Away building in Harlem 129th and Park. In Malmö there were only two more moves, to Kattsundsgatan 8, and finally Sandegårdsgatan in Limhamn. New spaces renewed the excitement in the studio and he was painting well.

A series of unique gallery exhibitions featuring expatriate African American painters and sculptors appeared in the nineties. Asake Bomani Gallery, San Francisco opened an extravaganza called Paris Connections (1992) and Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York opened By Their Choice (1994). Explorations in the City of Light (1996) opened at the Studio Museum in Harlem and traveled to the Chicago Cultural Center, Fort Worth Art Museum, New Orleans Museum of Art and Milwaukee Art Museum. Among group exhibitions were Three Masters: Ed Clark, Ernie Critchlow, and Herbert Gentry at Morgan State University Gallery; Baltimore MD; Free Within Ourselves at the Smithsonian National Museum of American Art in Washington, DC, Slow Art, PS 1, Long Island City, NY. The traveling Studio Museum in Harlem: 25 years at Payne Weber Gallery, was seen at 12 venues across the country.

Installation view of Herbert Gentry’s work at Ragnarpers in Gärsnäs, Sweden in 1993. Photo by Walter Backen

Installation view of "Explorations in the City of Light", The Studio Museum in Harlem, 1996

In Sweden, in the year 2000 Gentry suffered a stroke. It was the closing of the New York chapter of his life. He could not return for Overseeing the Seer (2000) which opened at Teachers College, Columbia University later that fall.

The paintings remaining in his Swedish studio were wrapped and shipped back to New York in September 2001. It presented the first opportunity to see his life’s work – done in so many different studios and places -together as a whole. Solo exhibitions continued at N’Namdi Gallery in Chicago and Norman Parish Gallery, Georgetown in DC. and he was included in several group exhibitions of African American Masters (1995, 2001, 2004) at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York City. The final chapter was beginning, but he was no longer directing the journey.

Since Gentry’s death in 2003 at age 84 in Stockholm, he has been honored with retrospective exhibitions: Face to Face (2005) at Phillips Museum of Art, Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, PA; Herbert Gentry: Moved by Music (2006) at the Amistad Center for Art and Culture at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, CT ; The Magic Within (2007) at James E. Lewis Museum, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD; Facing Other Ways: Herbert Gentry and African American Abstraction (2007) at Rush Rhees Library Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY; Herb Gentry: the Man, the Master, the Magic at Diggs Gallery, Winston-Salem State University in North Carolina; and Making Connections The Art and Life of Herbert Gentry (2014) at Boston University Art Gallery. His large painting “The Flag” was featured in the Smithsonian American Art Museum traveling exhibition African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era and Beyond (2012-2015).

________

1 (Brenda Delany, Herbert Gentry Interview: July 29, 1997, Audio Tape Transcription).

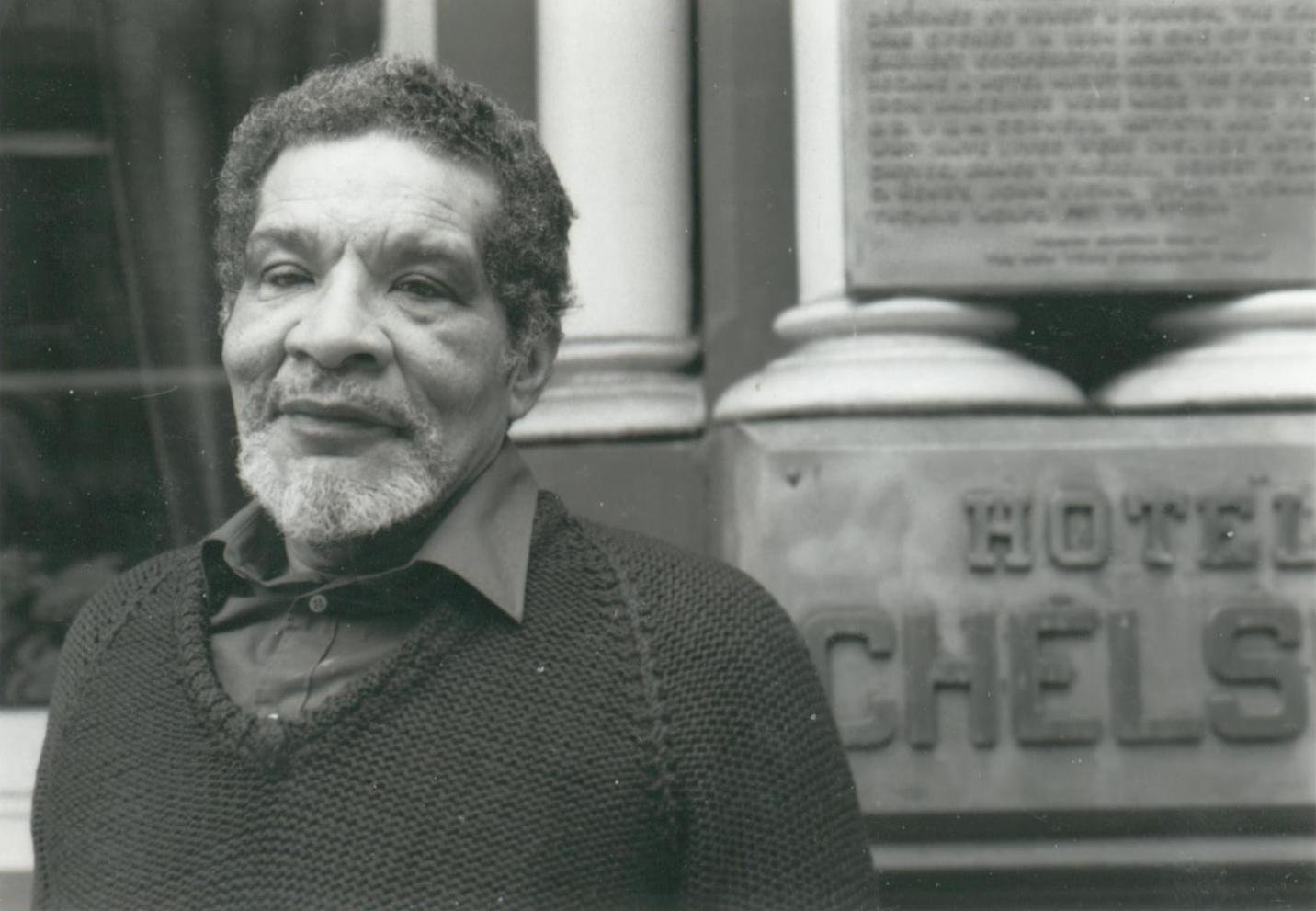

Herbert Gentry in front of the Chelsea Hotel, New York City, about 1990. Photo by Mary Anne Rose

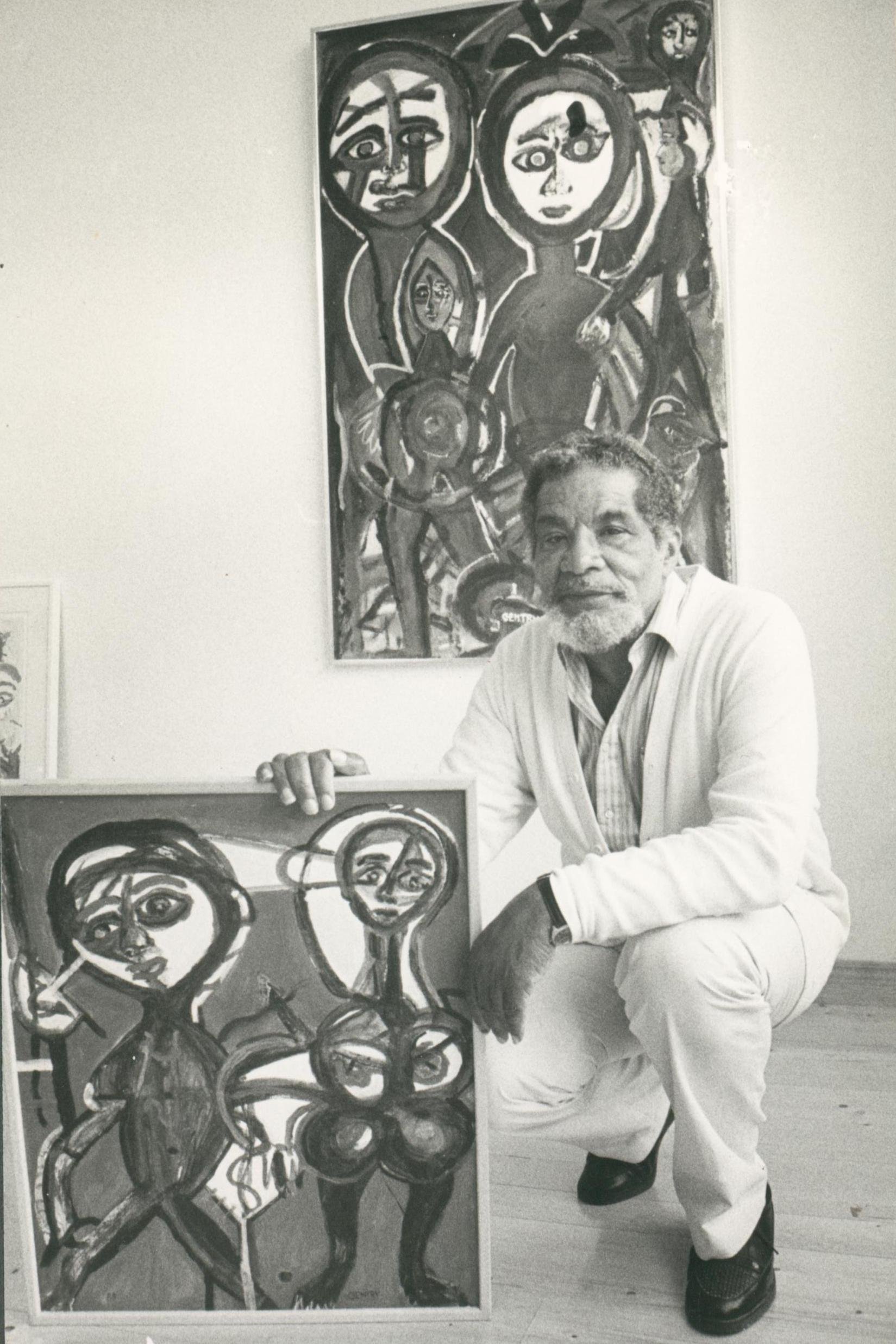

Herbert Gentry with paintings ©HD-FOTO HELSINGBORG Photo by Britt Marie Olsson